[1..] in Haskell

Shell interaction, signals, TTYs, jobs and the like are some of the core foundations that have been

around since the birth of time sharing operating systems but much of it is left in the literal 'black box', even

by developers! It can be quite complex when you start from the bottom up, but lets take a look at SIGPIPE,

it allows for some interesting shell interaction that often goes unnoticed but is immediately useful.

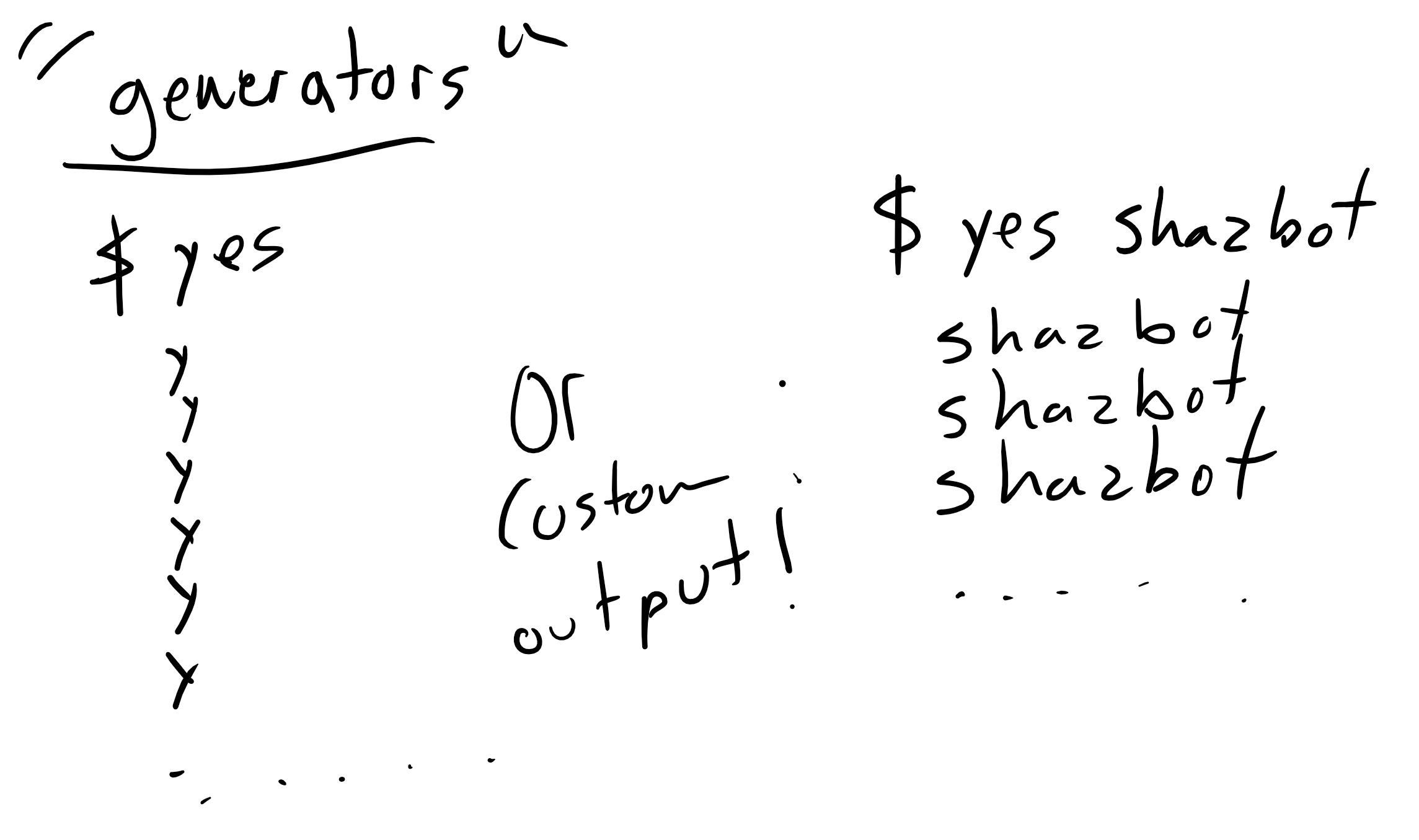

We start this example with a source of otherwise 'endless' input for all intents and purposes.

So called generators are a way to generate an infinite list of values, not unlike eg, [1..] in Haskell

The idea is to have something that will spew values as long as something is interested.

yes is probably the most simple of such programs, designed to generate 'y' that can be piped

to prompts and the such. The 'spoiler alert' here is that yes somehow knows to end its input despite

consisting of an infinite loop in code.

yes may sound like the most simple C program imaginable. It mostly is, the guts of the OpenBSD version essentially consists of this:

for (;;)

puts("y");

(full sources: https://github.com/openbsd/src/blob/master/usr.bin/yes/yes.c)

However in the GNU version (in coreutils) is more optimized for performance and locale handling, and ends up surprisingly different, with local buffering ahead of time and such: https://github.com/coreutils/coreutils/blob/master/src/yes.c

This is worth pointing out because when we dig in later with strace, there will be 'noise'

of these other operations in our investigation.

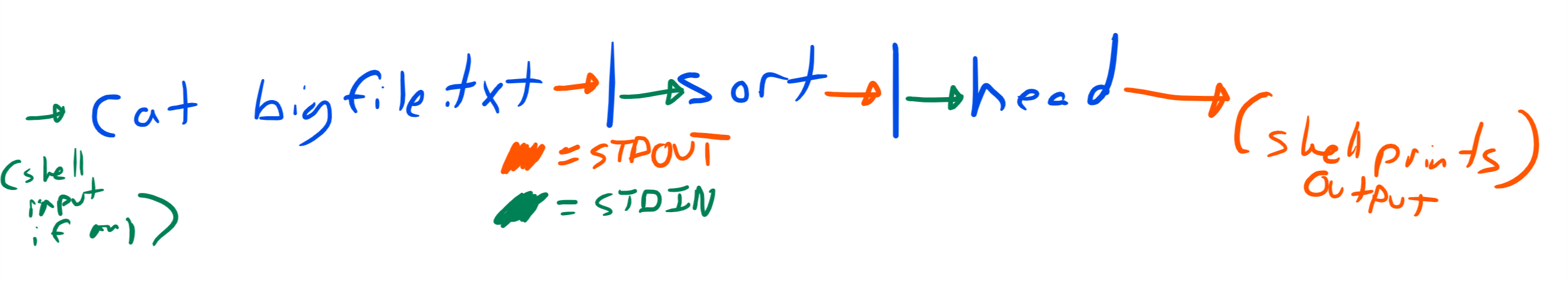

The writing mechanic, eg, puts(). writes to STDOUT which in this case has been rigged up through our job pipe.

Speaking of job pipes!

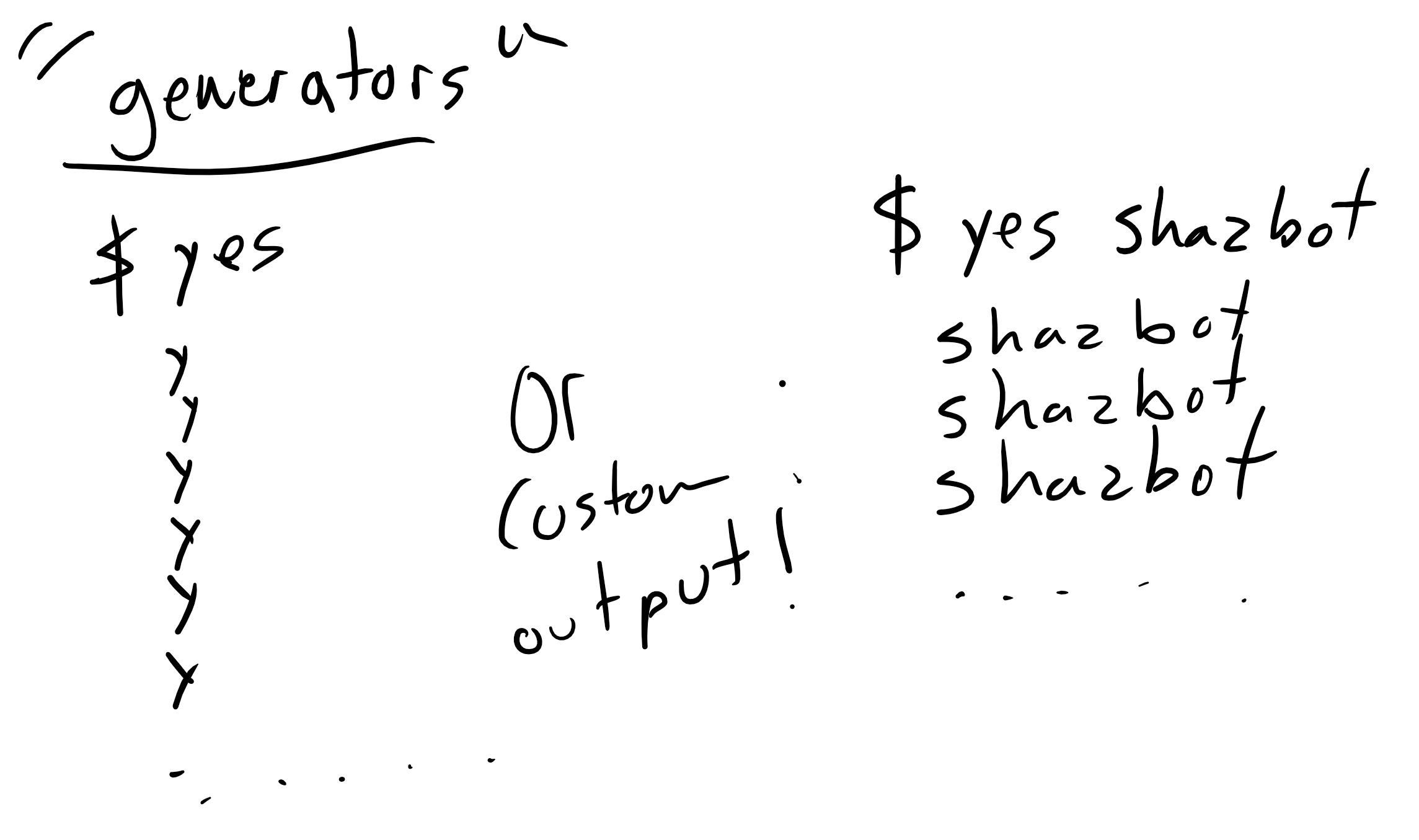

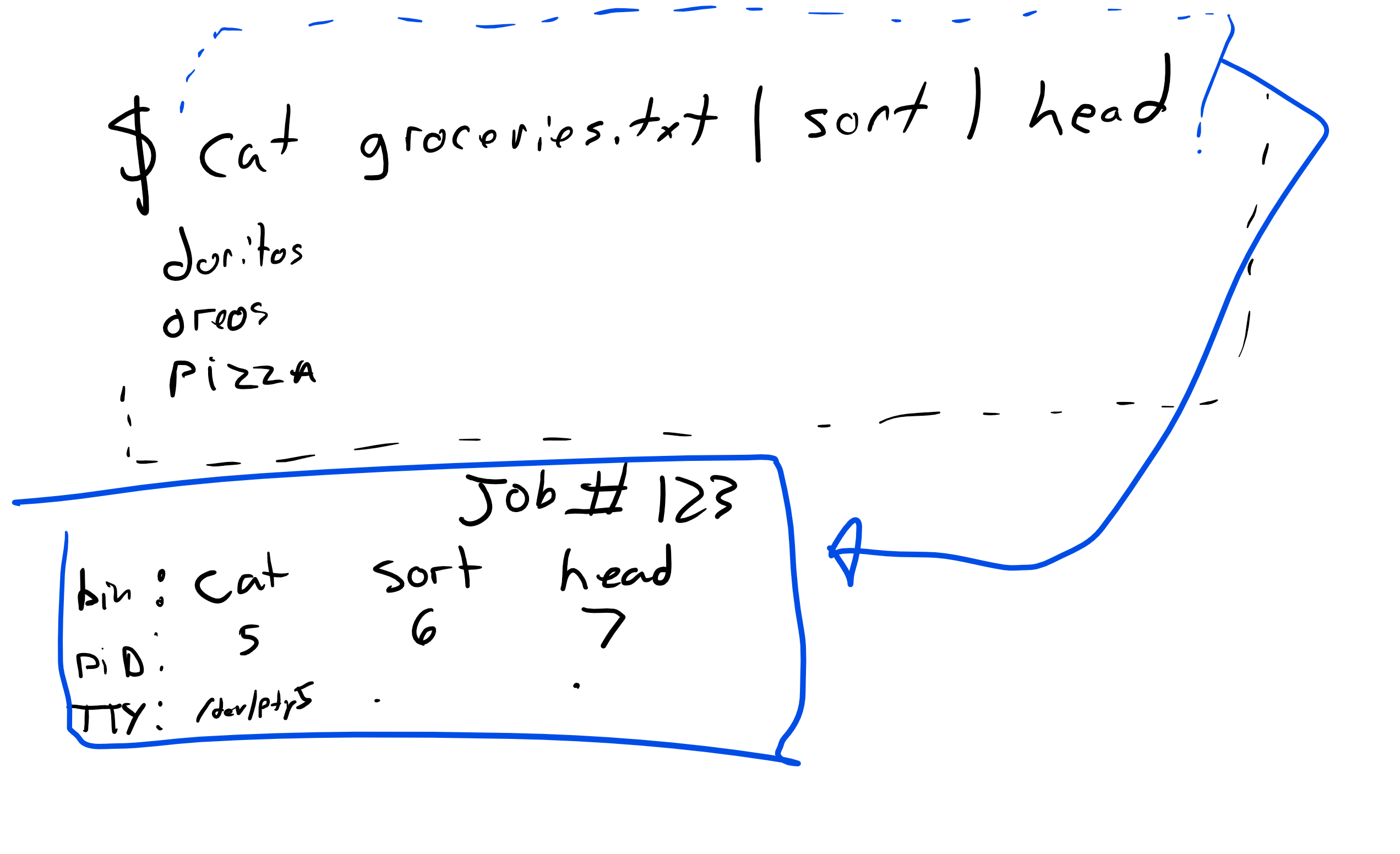

So with generators and yes in mind, we can use in shell pipes, which falls into job control. TTY handling, shell interaction

and job control is a very detailed beast I will not go into detail on here, but in layman's terms piping several commands

together sticks em together in a job (which is within a session). This allows the whole operation to handled discreetly

with signals, or 'bg', 'fg' and 'jobs' commands on any *NIX.

This is important to note because a job is created, a pipe handle is created to direct STDOUT

(by default, you can specify which with 2>&1 and so forth) to STDIN

between all the subprocesses of the job and we will see the handle id later.

For our purposes, just know the job creates a pipe to funnel STDOUT through. This is not technically completely correct

but if you know better put on your blinders (especially before seeing these doodles)

(sorry, done playing with wonky watcom since i can't analog-type anymore)

Running yes in a basic pipe, something like this:

dmh@beer-disposal:~$ yes | head

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

if only the people behind asking for raises during performance reviews were more like yes

Prints exactly 10 'y'. Why 10? thats the default number of lines head will read as you can see in man head

Yet, yes somehow knows to then terminate since no one is interested in reading the output anymore.

It seems to magically know when head is done. Changing the amount of lines head hovers up with eg,

yes | head -n2 works as expected, printing two 'y' lines and going back to your shell prompt normally.

But yes spews 'y' endlessly! How does it know when to kindly STFU?

This is handled with SIGPIPE! We can see this in the signal.h docs

"The SIGPIPE section denotes default action is 'T' (terminate) and 'Write on a pipe with no one to read it.'"

the write syscall docs also specify in failure conditions:

"An attempt is made to write to a pipe or FIFO that is not open for reading by any process, or that only has one end open. A SIGPIPE signal shall also be sent to the thread"

Before we get lost in the weeds, things like printf and puts use the write() syscall to actually..

write output. This is handled by the C runtime library!

Dry docs aside and ignoring non-essential details like buffered read/writes, here is what happens:

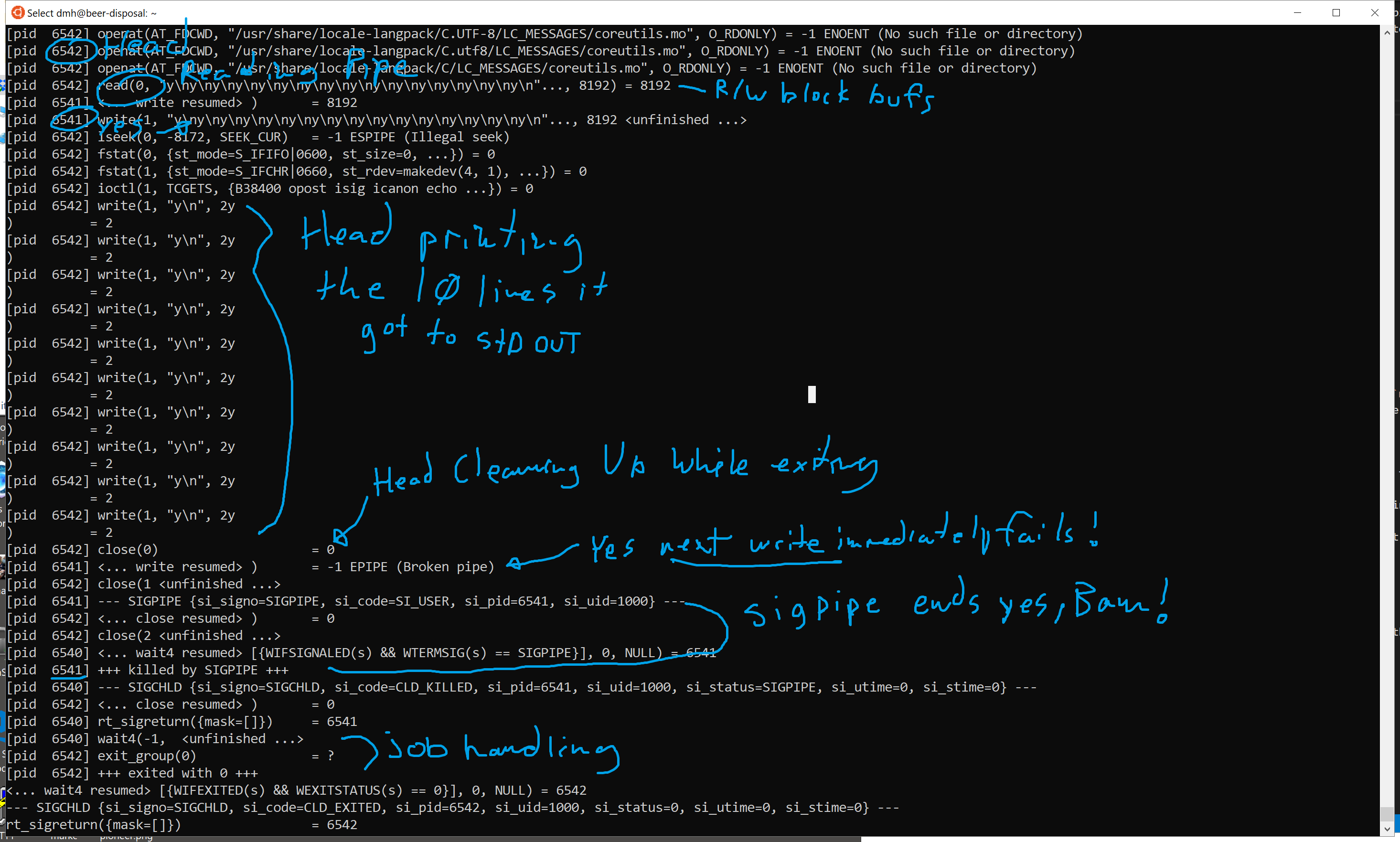

yes writes batches of 'y\n' repeatedly to STDOUT (which behind the scenes is a job pipe)head reads from STDIN (the pipe until it satisfies 10 lines and then exits (closing its handle to the pipe)!yes is still furiously trying to write to same pipe, next write since head exits returns -1.yes receives SIGPIPE signal itself and also exitsThis ignores some less important details like STDOUT line buffering and buffered read/write causing a difference in read/written bytes but it is not relevant to get the point of what is happening.

We can see this by running the pipe operation through strace:

dmh@beer-disposal:~$ strace -f sh -c 'yes | head'

Here is the important parts highlighted, pid 6541* is yes and pid 6542** is head

On a side note, you may notice lots of other things going on in the strace, that is because this is GNU coreutils yes, which as noted above does a lot of other 'stuff' in name of locale handling and performance.

A drastically better looking strace can be achieved on BSD systems for the motivated

The next time a haskell hipster is spouting the benefits of lazily computed infinite lists, let them know unix has had a pragmatic version of the same thing since before they were probably born!